Le Plébiscite de 1860

“La farce la plus abjecte qui ait jamais été jouée dans l’histoire des nations”

The Times, 28 avril 1860

Le Journal de Genève, 3 mai 1860

Reproduction de “The Times”, du 28 avril 1860

The Times, April 28, 1860 (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT).

GENEVA, April 23. Yesterday was the great day on whichSavoyhad to ratify the treaty of cession by popular vote, and I was debating within myself whether I should cross the Swiss frontier and sully your columns with a report of one of the lowest and most immoral farces which was ever played in the history of nations. I have been watching its dénoument for the last month, and you will find it excusable that I felt a surfeit of it. The absurdity of the whole comedy was such that while its novelty lasted one forgot its immorality to laugh at the ridiculous situations and incidents, and the seriousness of the actors in performing their parts. It was that kind of morbid interest which one cannot help feeling at the play of the cat with the mouse it has caught–those gambols and feats of activity on the part of the tormentor, encouraging the victim and then checking it again by one move of the claw, indulging all the while in the drollest possible antics, turning over now on one, now on the other side, creeping along the ground, and beating its sides with its tail or leaping up in the air, but never taking its eye off the victim. All this was droll enough in the beginning, but the poor mouse was so fascinated when it felt itself within the grip of its captor that it afforded but little sport, and when, nevertheless, it attempted to move, it received a blow which half killed it, and took away the wish as well as the power for further attempts. Thus the play was all on one side and became more disgusting than droll. I was not at all disposed to assist at the end of it, and thus give an importance to an act which deserved none at all. The timely arrival of some friends made me change my mind. They had assisted at the voting at Nice, and were so full of the drollery of the thing, and so anxious to see the counterpart of it, that I was tempted to make a joint expedition with them in search of fun.

They had started fromTurintoGenoawith a number of Nizzards, among whom were several of the deputies from that province, who wished to make a protest and demonstration on the spot. My friends were to have gone by the diligence, while the Nizzards intended to follow by sea. When the former went to the diligence office they were told that no more places were to be had. On this they asked for another diligence to be put on, on which the employé observed that they would have to pay for all the places. My friends, like eccentric Englishmen, assured him that they were prepared to do so, on which they were told that no extra carriage could be put on. At last a compromise was come to, by which they were allowed two places in the banquette, and in this manner they arrived at Nice, but alone, for the Nizzards had given up their idea of following. They found the town in considerable excitement, and the style of voting so free and easy that one of them was tempted to try and give his vote likewise. The voters came up in regularly organized detachments, marshalled by their authorities, and in the crowd the thing seemed by no means impossible. On the way to the polling place my friend met a free Nizzard who had two printed schedules, which he intended to throw in together. My friend asked him to let him have one of them, to which the Nizzard consented at once. Unfortunately, the moment was not well chosen, for there was no crowd, and therefore his unmistakably English appearance could not escape attention in a place where Englishmen are so well known, and, to his great regret, after some negotiation he was obliged to give up the idea.

The Nice experience of my friends looked rather promising, and we determined to see what sport might be had inSavoy. Our first idea was to go to Thonon. I confess that it was suggested above all by the facility of locomotion which the Sunday trips of the steamers on the lake afforded, and that a row was expected to take place there. But, knowing the circumstances, we did not give much credit to this expectation, and it was above all the greater facility and comfort of the steamer which decided us for Thonon. The steamer starts at half-past 8 a.m., and I was just finishing my breakfast, half an hour before that time, when my friends came in with the news that no steamer would start that morning. This was rather a good beginning, for it was the counterpart of the experience of my friends at the diligence office inGenoa. There was evidently a dislike to admit strangers to the proceedings, and a wish to transact the business of the day en famille.

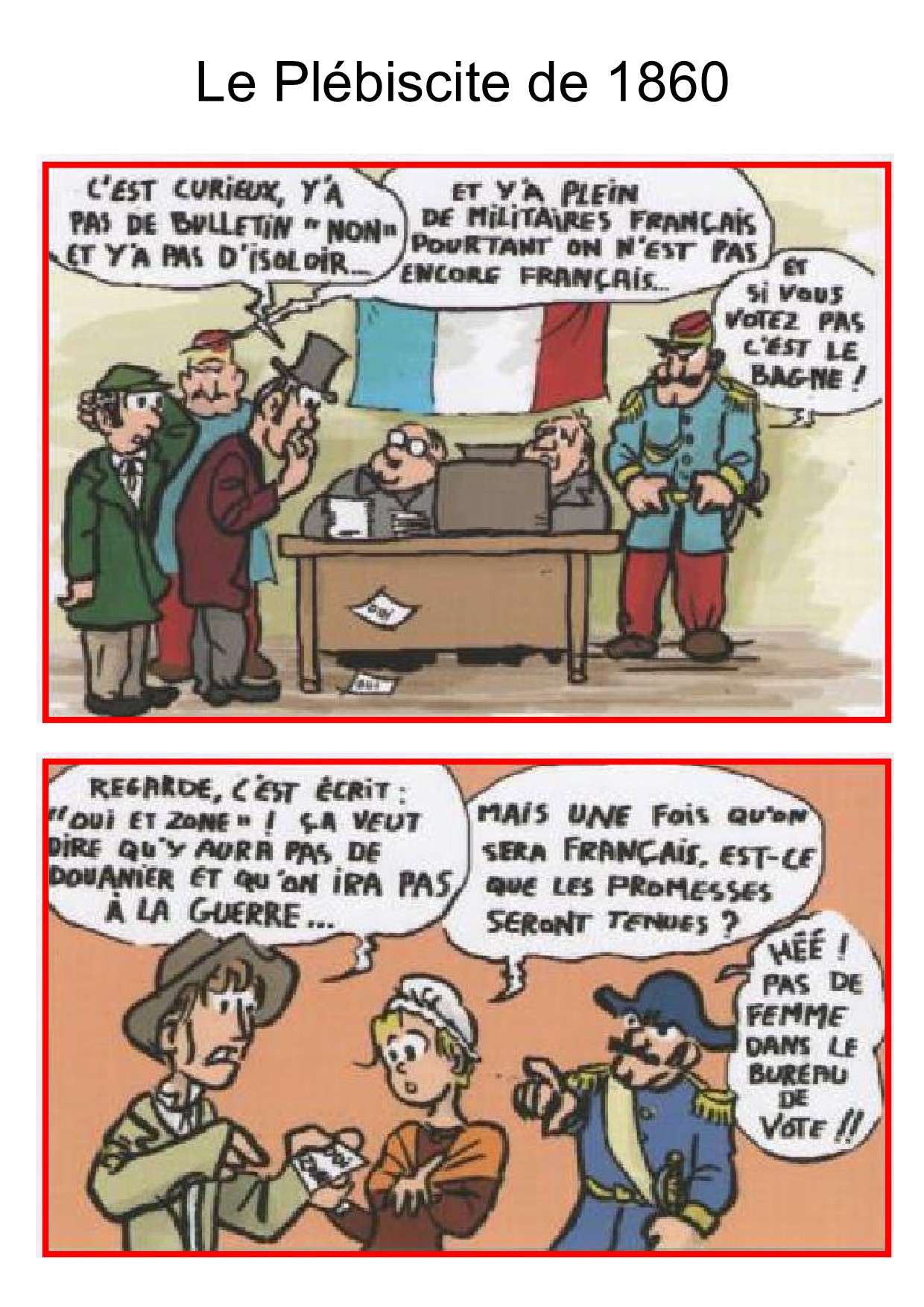

However, the weather was fine, and we determined not to be frustrated in our schemes, so we ordered a carriage for Bonneville, and started at 930 a.m. We had soon left behind us the few acres of the territory of Geneva, and passed through the narrow strip of the Customs’ zone, entering the Sardinian territory without any question being asked. The only incident was an inspection of our carriage by the douaniers before Annemasse. This latter town we found festively decorated with flags. There was scarcely a house which did not exhibit one or more French tricolours, which proved to us already, at the entrance, that M. Laity had arranged things inSavoyas well as M. Pietri at Nice. Otherwise the town had its usual Sunday appearance, people returning from church and stopping before the public-houses. Having toiled up the steep incline, after passing the bridge at Vetray, we reached Artlay and Nangy, where, to our astonishment, there was a scarcity of flags, which contrasted with the abundance at Annemasse. At Contamino things improved again somewhat, but all along the hillside to the left the scattered farmhouses seemed to have remained strangers to the proceedings. Above all, in descending towards Bonneville not a flag was to be seen, and the whole had a dead appearance that was striking. Evidently the attention had been concentrated on the chief place on the main road, above all Bonneville, the capital of Faucigny. Having not a month ago witnessed the strong opposition which then was manifested against the annexation toFrance, the festively decorated town was rather a surprise. In spite of the beginning of a snowstorm which had been following the whole way, the promenade on the place before the townhouse showed a good many idlers. Our appearance at this time of the year produced some sensation, and many a promenader was diverted from his walk to have a look at this unexpected arrival. Having ordered our luncheon, our first care was to inquire about some of the leaders of the opposition toFrance. One had gone toGeneva, another had accompanied him, and a third had gone none knew where. Altogether mine host, whose salle had been the head-quarters of the party, seemed far less communicative than last time. As we were, nevertheless, anxious to hear of what was going on, one of my friends, who had been here lately, proposed to see a little bookseller close by who had been always one of the loudest partisans ofSwitzerland. We were startled at tie door by the waving of a French tricolour, and my friend’s first remark was an observation on the subject. “Que voulez-vous ?” was the answer, “II y a un odre de la municipalité auquel il faut obéir.” The little man was evidently frightened. He told us how for the last few days the more prominent Swiss partisans had been mobbed, how one after another of those on whom they had reckoned had turned, and how most of those remaining stanch in their opinion, but, seeing the game lost, had left the place at the critical moment. He showed us his voting ticket. It was a printed card as a certificate that the bearer, whose name was on it, was inscribed on the list of the voters. Annexed to it was another printed card, about one-fourth of the first, with ” La Savoie veut-elle l’annexion à laFrance?” and below, “Oui et Non.” These cards had been printed by order of the municipality, and brought to the house of each voter by the Concierge de la Ville. Most of the leading members of the municipality were in the branch committee formed to agitate for the annexation. The former Syndic, formerly an ardent Liberal, but now known for his French enthusiasm, had been named for provisional Intendant of the province. Another enthusiastic French partisan had been named Syndic in his stead. Having thus the whole administration and with it the whole power of vexation in their hands, nothing had been neglected to bring about as satisfactory a result as any one could desire–promises, intimidation, with free use of Cayenne and Lambessa, all kinds of indirect influences, through women and relatives–in one word, every pressure was applied to demoralize the adverse party. We saw from our little friend how completely they had succeeded at Bonneville.

He did not seem to feel quite comfortable at our visit, and felt, no doubt, relieved when we left him for a stroll in the town. The first thing which attracted our attention was a quantity of proclamations posted up on the walls all about the place. We were almost startled at the barefaced way in which the functionaries called upon the people to vote forFrance. There were proclamations of the Governor of Annecy, of the provisional Intendant, of the Syndic of Bonneville, and of the Committees of Chambéry, all in the same sense, and with the same explicitness, showing the advantages of a connexion withFrance, reminding people of the promises made by the Emperor, and ending with “Vive laFrance!” “Vive l’Empereur!” The Governor of Annecy announces the arrival of the Emperor during the summer, and the Syndic convokes the citizens for the benediction of the French tricolour on the very morning of the election at 7 a.m. The municipal council, he says in his programme, will proceed in procession to the church for this consecration. All the electors are invited for the ceremony, which will precede the opening of the poll. In the morning the Hotel de Ville was to be decorated with the French national colours, the centre flag bearing “Zone et France” an example which all the inhabitants should follow.

Having read all these curious proofs of the liberty of vote and impartiality of the employés named byPiedmont, we were naturally anxious to verify them. But first we wished to see the voting, and accordingly we went through a dozen free citizens standing at the entrance of the Hotel de Ville, whom I suppose to have been national guards en negligé, from a little drummer who was standing among them. We made our way upstairs, and after passing a darkish window, we arrived before a glass door looking into the polling place, where half a dozen men were in warm discussion, behind a wooden railing which divided the room in two, and before which a free Savoyard was just giving his vote. Of the urn we could see nothing, for it was behind the railing and unapproachable to the voter. Wishing to see the thing more closely we were on the point of entering, when we were stopped by a policeman, who asked us what we wanted. We told him that we wished to see the proceedings, on which he told us that he must ask for permission. In he went accordingly, and a consultation ensued among those behind the railing, at the end of which two persons came to the door, one of whom asked us the same question as the policeman. We told him our errand, on which he told us that no one who was not provided with a schedule could enter the room. His evident unwillingness to talk disposed us to be very amiable, and we asked him question after question, whether the voting was over, how long it lasted, &e. He answered civilly enough that the voting would last till the next evening, and I was just going to ask why when the other individual, who had accompanied him to the door and had not spoken yet, snorted out in a rude passionate manner “Eh bien, si cela vous intéresse, 4•5ième des électeurs ont déjà voté.” We thanked him civilly for his information and telling him that we had seen what we wanted, we went away highly amused with our trip to the Hotel de Ville.

We had tried to swallow some warm water, presented to us as soup, and were just trying to work our way through a piece of stringy, tough bouilli, which neither salt, nor mustard, nor pickles could season, when a tramp was heard outside, the door opened, and let in two gendarmes, with a policeman behind them; they advanced gravely to our table, and, saluting, demanded our papers. It was rather strange that, having been allowed to enter the Sardinian territory without any question being asked, we should have this visit in the middle of the country. By a fortunate chance we all had our passports with us, and gave them up, and continued our operation on the beef, unheeding the mumbling which was going on close by. This lasted for several minutes, showing evidently the wish to find faults with our papers. All at once the gendarme who had my passports said that there was no Sardinian visa. Now, there happened to be two instead of one, and, taking the passports rather roughly out of his hands, I pointed to the two visas, on which the authority said, in a grave, agitated tone of voice, “Take care, Sir, what you do.” I looked up, and saw the passport shaking in his trembling hands. The poor follow, a Savoyard into the bargain, was ashamed of the part of bully which he had been ordered to play on inoffensive travellers.

Some more minutes were passed in examining, deciphering, and mumbling over our passports, the conclusion being that we all ought to have a visa of the Sardinian Consul atGeneva. The remark was so absurd and untenable that we could not help laughing, and probably the authority was of our opinion, for we were soon left to ourselves, not a little pleased by this bit of experience, which will, I hope, serve as an encouragement for those who should be inclined to visit Chamouni when its approaches are once guarded by French gendarmes.

We remained at our luncheon, but heard afterwards that the police and gendarmes went to cross question our coachman who we were, what we were doing, whether the carriage was ours, and other similar inquiries, to all of which our coachman, at least according to his own account, answered by pleading general ignorance. The authority evidently felt uneasy; how much more would they have done so had they known that their proceedings will figure in your columns, as a proof of the liberty of theSavoyvote!

After luncheon we had the visit of one of the remaining Swiss partisans, who confirmed all the little shopkeeper told us about the pressure. The letters and papers had been stopped; no proclamation of the adverse party was possible, for men had been paid in advance to prevent the pasting up or tearing them down. The hopelessness of the struggle had demoralized even some of the most ardent partisans ofSwitzerland, and every moment news came in of other defections. Almost all the candidates of the Liberal party for Parliament had voted, and it was merely in the out-of-the-way villages and farms that the opposition continued. Five Syndics had been deposed the day before the voting at Frangy, Chablais, Savigny, and two other places, and their posts taken by men devoted toFrance. Mobbing was freely resorted to, and while coming to see us our friend had a tail of gamins after him crying “à bas la Suisse.”

We had had enough all of us, and, the carriage being ready, we shook hands with “the last of the Mohicans” and started. The weather had cleared up again, and, satisfied with our tour, we commenced gaily our journey back, and it was with a feeling of unavoidable relief that we crossed the frontier of the Helvetic Confederation.

I leave you to draw your own conclusions from this trip, which will show clearly what the vote was in this part ofSavoy. The vote was the bitterest irony ever made on popular suffrage. The ballot-box in the hands of those very authorities who issued the proclamations; no control possible; even travellers suspected and dogged lest they should pry into the matter; all opposition put down by intimidation, and all liberty of action completely taken away. One can really scarcely reproach the Opposition with having given up the game; there was too great force used against them. As for the result of the vote, therefore, no one need trouble himself about it; it will be just as brilliant as that in Nice. The only danger is lest theSavoyauthorities in their zeal should fare as some of the French did in the vote of 1852, finding to their surprise rather more votes than voters inscribed on the list.

This article was also published on the 3rd of May 1860 in French in the Journal de Genève.

The voting ballot "Oui et Non" is a mistake. Voting ballots in this area had on them "Oui et Zone" in reference to the free-trade zone which was to be created. In the french version of this letter published in the Journal de Genève, it is "Oui et Zone".

Ficher Pdf du Journal de Genève du 3 mai 1860 reprenant la traduction du Times du 28 avril 1860 téléchargeable ci-dessous